Magic Lantern

Zachary Fabri, Benin Ford, Fabienne Lasserre, Jonathan Miralda and Andrés Villalobos, Richard Roth, Carolina Saquel, Maria Walker

Curated by Calvin Burton

November 11 - December 11, 2022

Opening Reception: Friday, November 11, 6 - 8pm

Performance by Zachary Fabri: Sunday, November 20, 2:30pm

For the mass loomed before her; it protruded; she felt it pressing on her eyeballs.

-Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse

-Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse

A parable tells the story of a group of blind men who have never heard of an elephant and are given an opportunity to imagine what an elephant is by touching one. Approaching from different sides, each man touches only one part of the animal’s body—trunk, leg, tusk, torso—and arrives at a different conclusion: it must be a snake, a tree, a spear, a boulder. Each man is convinced he is right and the others wrong.

It isn’t possible to apprehend the whole picture, so we work with the parts available to us. Our mind tends to make sense of the unfamiliar by reaching for the familiar, creating ballast in an unsteady world. And so the center of things eludes us. But while the mind is adept at interpreting experience, our bodies remain subject to forces beyond our ability to rationalize or explain. In the realm of the sensory, then, we may hope to find alternate routes, through a broader array of perspectives and towards a deeper awareness of the relationship of parts to whole.

This exhibition gathers work that suggests a connection between the body and its surroundings through the senses of sight and touch, and their conflation in the haptic. Haptic seeing, or “touching with the eyes,” is a form of close viewing (in contrast to “optical” vision, which can be understood as seeing from a distance). As described by psychologist James J. Gibson, “the haptic is the sensory system through which one feels an object [relative] to the body and the body relative to an object… and by which… one is literally in touch with the environment.” Haptically-charged objects implicate the body, both in their form, and in their reception by the subject. Bypassing the brain, such objects act directly upon the central nervous system, placing bodily sensation at the center of experience.

Painting and video both carry a tension between what we see and what is there. For painting, such tension is rooted in the co-experience of two and three dimensions. Richard Roth’s small painted cuboids amplify this paradox by integrating precisely-scaled geometric motifs across the rectangular facets—front, sides, bottom, top. While the crisp, hyperflat (almost virtual) surfaces seem contrived to provoke a purely optical response, the extension of volume into the viewer’s space subverts our tendency to merely look; we must contend with an object. The paintings seem to follow us as we move through the room.

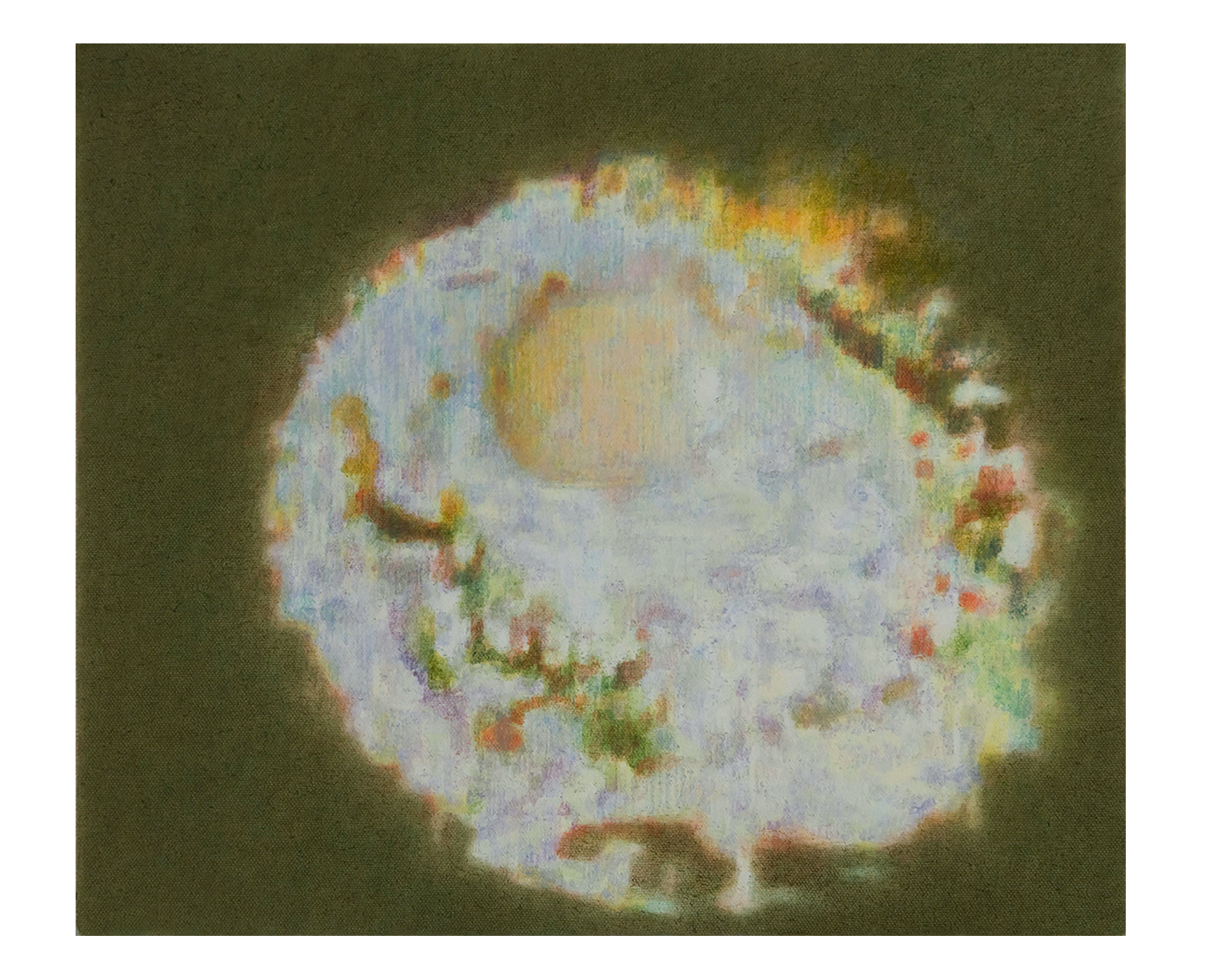

Whereas Roth’s calibrated design pushes seeing to the point of touching, both Maria Walker’s and Fabienne Lasserre’s processes move from the opposite direction: intuitively, through contact with materials. Walker sets up the formal conditions for her paintings prior to stretching the canvas by “drawing” on the stretcher with protruding pieces of wood. The resulting topography—often in a circular arrangement, with a combined centrifugal and centering force—subjects thin washes of color to the contingencies of gravity and viscosity. Acutely human in scale, these paintings compress time, and the flow of feeling and emotion that accompanies it, into matter. Lasserre welds her steel supports and incorporates other industrial elements, such as vinyl and fiberglass, inscribing visceral form and gesture within soaring curvilinear vectors. These conjunctions of weight and flight, like a dusty window (or mirror or lens), prompt the viewer to see something beyond (or through) the frame, while asserting their place in the world of objects.

Benin Ford approaches the tradition of oil painting with images drawn from the TV shows of Black American popular culture of the 1970s and 80s that he grew up on, including Roots, Good Times, What’s Happening, and The Cosby Show. Not taking the image for granted, Ford brings renewed forces to bear on the protocols of representation, levering his sources towards a deeper reconstruction, layer-by-layer, of television light itself. Materializing the ephemeral glow of cathode ray tubes, the artist coaxes rote scripted moments into haunted fragments of memory.

Zachary Fabri's and Carolina Saquel's use of the moving image also activates possibility within, and for, the senses. In Fabri’s video Mim Andar Avenida Canadá, filmed during a residency in a rural area of Minas Gerais, Brazil, the artist walks through a desolate industrial field, his all-white clothes collecting iron-rich dust. The camera, framing orange ground and blue sky, follows a body in rhythmic motion, exchanging physical traces, and ultimately merging with, the external world. For Back to Front Landscape, Saquel fixed a camera to the back of a car to film the dust cloud produced while driving on a dirt road in Sardinia, Italy; in the final video this footage is played in reverse. As it elongates the moment of becoming, the piece also depicts an obscuring of vision, evoking the limitations of sight conveyed by Wallace Stevens in Poem Written At Morning:

The truth must be

That you do not see, you experience, you feel,

That the buxom eye brings merely its element

To the total thing, a shapeless giant forced

Upward.

Fabri’s video also incorporates reverse playback, which, like Saquel’s work, draws attention both to the physics of the camera and the composition of the material filmed—for both artists, dust. Fabri’s tossing of dirt into the wind, inverted, becomes a capturing of clouds, and suggests a return to the earth of the extracted iron for which this mining region is known. Saquel’s simple gesture, meanwhile, synthesizes past and future time, leaving us in a perpetual present, as if our eyes were seeing for the first time.

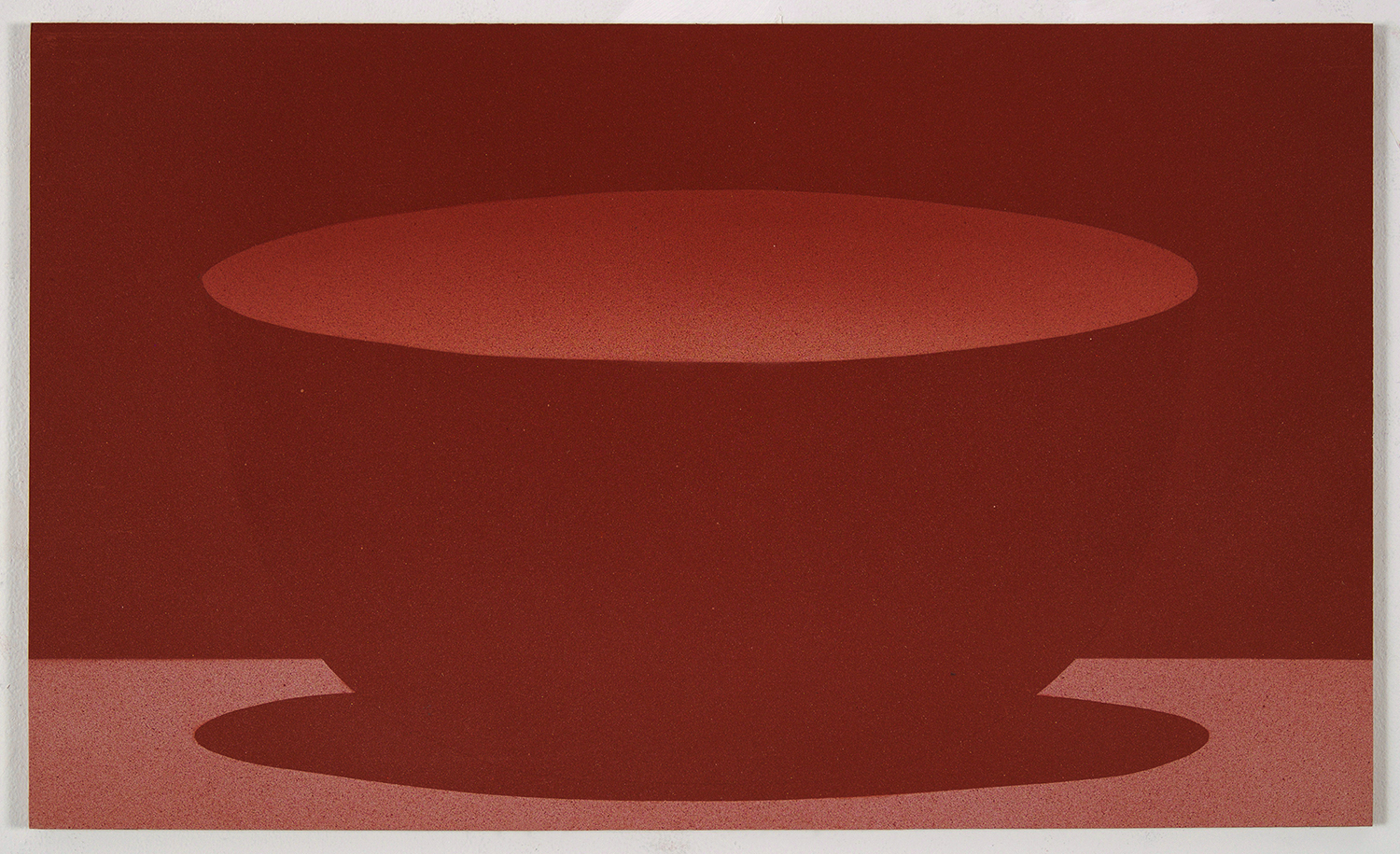

If dust is both a subject and an object in the videos, it is also the basis for the pigments used in paint and ink. Suspended in liquid and spread across a surface, pigment doesn’t lose its geological valence, even as it is received by the eye as color. Andrés Villalobos and Jonathan Miralda activate this condition explicitly in their collaborative Perfume series, which presents vignettes and light phenomena drawn from the layered urban experience of Mexico City. In these drawings, the projected “dust” of the airbrush becomes an analog for the function of the eye: particles of light passing through the pupil become particles of pigment sprayed from a nozzle; a projection of light becomes a projection of matter. The nature of dust is to reveal as it conceals; simultaneously of earth and air, it presides over the exhibition.

The title of the exhibition refers to a technological predecessor to the stereopticon and stereoscope. Two identical "slides" (which, prior to the invention of photography, were hand-painted on glass) were projected together on a wall to create a “three-dimensional” image. The light source for the projections was originally a flame (the "lantern"). It is tempting to imagine that these images, though composed purely of light, were in fact corporeal, and that this momentary embodiment of form, though explicable in scientific terms, could not be completely extricated from the presence of some unknowable force, what some might call “magic.”

The materialization of sight (or visualization of touch) is more than just the co-experience of two senses—it is closer to a new (sixth) sense, a kind of supra-sensorial activity. Such sensory amplification pushes us beyond knowing in the conventional sense to a point where we can no longer rely on our cognitive faculties—a short-circuiting of the mind’s ability to convert experience into knowledge. Connecting with the unknowable, we unlearn something, leaving space for alternatives to understanding, and even possibilities for reconciliation.

– Text by Calvin Burton

Images: Carolina Saquel, Untitled (Landscape), photography. 2014–2016. Reflections upon landscape, vision, movement /stillness. Dust. The repetition of (almost) the same. 2018.

______________________________________________

Zachary Fabri is an interdisciplinary artist engaged in lens-based media, language systems, and public space, often complicating the boundaries of studio research, and social practice. This context specificity often yields work that includes video, performance, photography, installation, and design. He is the recipient of awards that include The Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Award, the Franklin Furnace Fund for Performance Art, the New York Foundation for the Arts fellowship, and the BRIC Colene Brown Art Prize. Fabri’s work has been exhibited at Ludwig Museum (Budapest), Recess (Brooklyn), Art in General (NY), The Studio Museum in Harlem, El Museo del Barrio (NY), The Walker Art Center (Minneapolis), The Brooklyn Museum, The Barnes Foundation (Philadelphia), and Performa. He has collaborated on projects at the Museum of Modern Art (NY), the Sharjah Biennial (UAE), and Pace gallery (NY). He recently completed a solo exhibition at CUE Art foundation in 2022 in New York.

Benin Ford was born in Memphis, TN, and is currently based in Brooklyn, NY. He was a recipient of the Joan Mitchell Foundation’s Painters and Sculptors Grant in 2013. Ford has recently collaborated with choreographer Nia Love on the research platform and serial performance project g1(host), concerning the material and gestural afterlives of transatlantic slavery. His current painting projects continue to explore the political and visual unconscious of 1970s and 80s commercial network television. His current writing projects include an extended essay on the resonances of J. M. W. Turner’s Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On and contemporary black art and thought. He has guest lectured at New York University and the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He received an MFA/MS in Painting and Art History from Pratt Institute.

Fabienne Lasserre, a 2019 John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship recipient, received her MFA from Columbia University. Her recent show, Eye Contact, TURN Gallery (NY), was reviewed by Anthony Hawley in artpapers. Other recent exhibits were held at Hallwalls Contemporary Arts Center, (Buffalo); Parisian Laundry Gallery (Montreal); and Palazzo Costa Tretenerro (Piacenza, Italy). Two-person exhibits include Safe Gallery, with Annette Wehrhahn (NY), and 315 Gallery, with Ezra Tessler (NY). Lasserre has participated in numerous group exhibitions including Ceysson de Bénétière (Luxembourg); Contemporary Arts Museum (Houston); Museo de Antioquia (Medellin), and Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal. In 2017, she was awarded the Saint-Gaudens Memorial Fellowship to produce two outdoor sculptures for the grounds of the park. In 2016-17, she received a Sharpe-Walentas Studio Program award. She is Director of the low-residency graduate program MFA in Studio Arts at MICA in Baltimore. Lasserre lives and works in Brooklyn.

Jonathan Miralda Fuksman was born in Mexico City, where he currently lives and works. He received his Bachelor's degree in Visual Art from the ENPEG "La Esmeralda" in Mexico City. He has received grants from FONCA (2009, 2010) and la Fundación Colección Jumex (2007). Exhibitions include guadalajara90210 (Mexico City); Museo del Pueblo de Guanajuato; GAM (Mexico City); Museo Carrillo Gil (Mexico City); MUSAS (Sonora); Estudio Marte 221 (Mexico City); Galería MERCADO NEGRO (Puebla); Galería Toca (Mexico City); Paseo de las Artes Pedro de Mendoza (Buenos Aires); and ESPAC (Mexico City).

Richard Roth’s work has been exhibited nationally and internationally. His exhibitions include Valletta Contemporary (Malta); Galerie Rob de Vries (The Netherlands); The Suburban (Oak Park, IL); Rocket Gallery (London); the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts; Reynolds Gallery (Richmond, VA); Feigen, Inc. (Chicago); the Whitney Museum of American Art (NY); OK Harris Gallery (NY); and Castelli Warehouse (NY). In 1991 he was the recipient of a Visual Artists Fellowship in Painting from the National Endowment for the Arts. He is the co-editor of the book, Beauty is Nowhere: Ethical Issues in Art and Design. His debut novel, NoLab, was published in 2019 by Owl Canyon Press. He received an MFA from the Tyler School of Art and a BFA from The Cooper Union.

Carolina Saquel is a Paris-based visual artist and former lawyer. In 2003 she was selected in Le Fresnoy (France), a two years program that focuses on crossing fields between contemporary art and cinema. She uses the moving image as a medium for altering perceptions of temporality of seemingly unimportant events. Bodily gestures, the history of painting, nature stripped of human presence and cinematographic as well as literary references are points of departure for her video and photography. Her work has transitioned from reflections on painting- the frame as a window to the world- to what could be considered a sculptural use of the moving image. Included in various private and public collections internationally, her work has been shown in exhibitions and film/video festivals and screenings around the world, including Espai 13, Fundació Joan Miró, (Barcelona); Kadist Art Foundation (Paris); Harbourfront Centre (Toronto); Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de Strasbourg; Grand Palais (Paris); Espace Culturel Louis Vuitton (Paris); Bloomberg Space (London); and Württembergischer Kunstverein (Stuttgart).

Andrés Villalobos Cuevas was born in Mexico City, where he currently lives and works. He received his Bachelor's degree in Visual Art from the UNAM. Villalobos has participated in various collaborative projects, including the Taller de Imágenes en Movimiento del Centro Multimedia (2000, 2006), and he was a founding member of the artist cooperatives Cráter Invertido (2012-2020) and Vacaciones de trabajo (2019-present), and has been a member of Arts Collaboratory Network since 2015. He has published three book collections through funding from FPCC (2015, 2018); has organized two animation conferences with support from IMCINE (2016, 2017); and has received various grants from FONCA (2017, 2016, 2014, 2003). He is currently editor of Siempreeshoy, a collective newspaper. Exhibitions of his work include Documenta 15 (Kassel), Museo Carrillo Gil (Mexico City), MUSAS (Sonora), Leopold Museum (Viena), Galería Toca (Mexico City), Gwangju Biennal (Korea); Yakarta Biennial (2015), Venice Biennal (2015), Museo Universitario del Chopo (Mexico City), and Museo de Arte Moderno (Mexico City).

Maria Walker received her MFA in Painting from Tyler School of Art and her BA in Visual Art from Brown University, where she also completed a Capstone Project in Poetry. In 2011 she attended the Skowhegan School for Painting and Sculpture. Walker’s work has been published in the Smithsonian Magazine and reviewed as a Critic’s Pick on Artforum.com. Her paintings and poems have been featured on numerous other sites including The Brooklyn Rail and New American Paintings, and her work has been shown widely in the United States, including in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Provincetown. Walker lives and works in Bronx, NY.

Calvin Burton lives and works in Brooklyn. Previous curatorial projects include Present Company (Brooklyn) and Spring Break Art Fair (New York). Exhibitions of his work include Reynolds Gallery (Richmond), Tappeto Volante Projects (Brooklyn), Present Company (Brooklyn), Jack Hanley Gallery (New York), Cuchifritos (New York), Branch Gallery (Durham), Samson Projects (Boston), The Bronx Museum (Bronx), ADA Gallery (Richmond), Raw & Co. (Cleveland), Second Street Gallery (Charlottesville), and Galería Ramón Alva de la Canal (Xalapa).